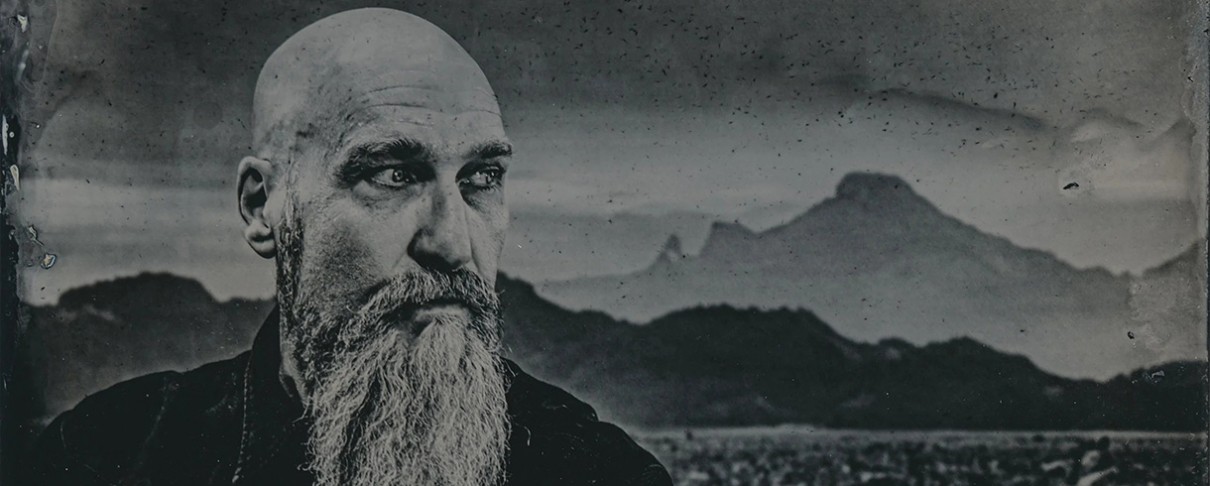

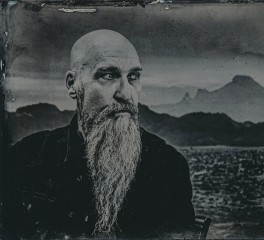

Steve Von Till: "In this music we don't avoid darkness, we stare it in the eye and seek community"

An immersive conversation with an extraordinary human and musician

Steve Von Till likely means as much to you, the reader of these lines, as he does to me. The man who first touched our souls with Neurosis, and later with his solo music as well as the Harvestman project, naturally carries within him great depth and sensitivity. Meeting him at the Roadburn Festival gave me the courage to approach him for a conversation-a courage to which he responded with genuine joy and interest.

This conversation evolved into a collection of stories. Steve doesn’t answer questions directly. On each topic you open, he begins to tell a story so vividly that you hang on his every word, letting his narrative carry you along, seeing the scenes he describes come alive before your eyes. Unfortunately, I cannot convey the emotion in his voice, but below you will find several themes that Von Till explored extensively. And despite the length of our conversation, I guarantee you won’t get enough.

His personal band, Harvestman project, the Roadburn Festival, the Fire In The Mountains Festival, the cultural legacy of Neurosis, mental health, poetry, the past and present of music-all find their place in the life of this multifaceted man, who, among many things, is also a teacher and deeply passionate about his work.

I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did and that we soon get to see him live on a stage, where we can be moved to tears by his deeply emotional music.

We're over here on the last days of August with Steven Till, and we are starting to do a conversation about his latest doings, both musically and in other projects. How are you, Steve?

I'm good. How about yourself?

Very good. Thanks for asking. So we had α little chat before and summer actually found you all over the place. It find you in Europe, it found you in the Pacific Northwest touring. And now you're back in your hometown, ready for schools to start - for anybody that doesn't know, you're also a teacher aside of a musician. Βoth aspects are very important to your work. And how do you feel? Are you ready for starting a new year?

Yeah, always. I mean, I always say I'm never ready, but I'm always willing. So it's going to happen whether I'm ready or not. And I give it my best.

That's pretty cool. So you had a new album out this year, "Alone In A World Of Wounds" with your solo project. And you toured vastly for the new record. How was this experience? How is the reception of the album from the people is getting to you?

Yeah, For me, it's my most important record I've ever made. It feels like my most emotionally personal, my most musically and vocally evolved version of my own music. As I'm getting into my mid-50s, I'm feeling like, in a lot of ways, this is my most inspired time that I've ever had as a musician, as a writer, as an artist, as a singer. even admitting to myself that I am a singer. So I feel like I'm really putting myself out there in a really open way. I feel more sensitive in life in general to the energies around me, to the energies within myself, and I feel I'm putting that out there in a real raw way.

What's been really fulfilling for me is the connection as I've been traveling around and talking to people and singing for people, and it really is making a connection with those people that are open to it. And that's what means everything to me, when people walk up to me and they tell me about how it really hit them right where they needed, right where they needed it to, to get through a moment of grief or sorrow or loss. which are, overriding themes within my music all the time. But I think specifically in this record, it's very evident. And like I said, it's right there on my sleeve, wearing it open. It makes me feel more connected to the greater aspects outside of myself, when people come up and connect with it.

That's what means everything to me, when people walk up to me and they tell me about how it really hit them right where they needed

I feel like being creative like this is when I feel most connected when I'm composing the songs or singing the songs or actively recording them. That's when I feel most connected with the creative spirit of the cosmos. That's when I feel like I'm going with the flow of the universe that I'm supposed to be in. where I'm able to be my true self, my authentic self. And that comes out mostly through art and music, because in regular life, we have to put on a lot of armor and put on a lot of walls and barriers to protect ourselves in this world. And musically is when I feel most open. And to know that other people are feeling it, other people are getting it, other people are connecting with me through my art, and we're both connecting together. to this thing that's larger than any sort of performer or artist or recording, but to these energies out there in the world, that's what makes it all worth it to me, is that connection.

I see. Well, what it really inspires me to ask through this question is that beforehand, the previous year, you released in some intervals, basically full moon intervals, α big, big work with your other project, Harvestman, that's called "Triptych", which was basically a three-part album with very robust dark sounds coming from outer space. Did that Triptych project help you find this connection with yourself a little bit more in order for you to be able to return and release the latest Steve Von Till record?

Not totally, because they were happening at the same time. I mean, the Harvestman material, some of it was recorded right before I turned it in. Some of it was recorded over the last several years, and a few of the pieces were even recorded 20 years ago or a little bit more than 20 years ago. So it's, that's kind of material like out in my home studio that sits around in the laboratory and waits for its moment to reveal itself to me of what it's asking me to do, because some of it predates my last couple of Harvest Men records. And some of it is brand new. And that was more of a body of work that just kind of slowly gathered like moss on the side of a tree. And once the sunlight hit it and from a certain angle, they all seem to be in groups of three. That's when I realized it needed to be a triptych, when I had all these songs of different types, but they all had two brothers and sisters.

Why did you release, why did you decide to release them in three different full moons of 2024? What was the significance behind that?

I knew I had to get them out quickly in order to make room for the solo record, which I was also finishing. I didn't want them to be stepping on top of each other. When I was thinking of how to, you look at a calendar, part of it was just logistics, like looking at a calendar year and thinking, okay, how am I going to divide a calendar into three in some sort of way that feels compelling and that honors the music? And I knew when I needed to have it start, and I knew when I had to have it end. I was just looking at the calendar. I'm always paying attention to the moon. I think the lunar calendar informs as much as the solar one does. In fact, our ancestors used combinations of the two. They both marked different aspects of what our roles were at that certain time of the year and defining certain seasons and what happens during that time of the year. So I looked at the months that I thought would be best and looked at what those full moons would be, and that just became the plan.

That's great. Well, since you said that a lot of the music inside "Triptych" was created almost 20 years ago, it is something that I always wanted to ask you. What is the connection between what you did with Tribes of Neurot? I feel some inspiration and some connection with the earliest Harvestman, especially records like "Adaptation and Survival". I see that some of the things that you were trying to do in the Tribes of Neurot project went on within you and got into the new thing. Is that the case or am I falling off?

Well, they're only related in a sense that Tribes of Neurot also kind of evolved initially from a home studio idea. I've always had a home studio since I was in high school, since I was a teenager. And I've always played with sound. And that was that was part of the driving force of Tribes of Neurot was, I was doing that and some of the other guys were doing that. We decided to just bring it together and also improvise in the rehearsal studio.After a while, we didn't feel inspired to continue that. I'm not sure for what reason. We weren't around each other as much as we were when we were younger. We were gonna spend time to get doing our main project, not a side project.

I don't remember what year my first Harvest Men record came out, but some of those songs were already collecting at home, even way back on my cassette four track days. It's always been more of an attenuation of my kind of psychedelic home recording, like, lo-fi and high fidelity, like following an inspired moment down a rabbit hole and seeing where it goes. And sometimes something happens and I get something instantly, and sometimes there's an interesting idea, but it doesn't go anywhere, so it sits. It sits until maybe 10, 15 years later, I'll open that session up or put that tape on or listen to this thing and see. And with a new perspective and fresh eyes and fresh ears, then it finds its home, it finds its place, and new things come on top of it, it combines with new ideas.

So it's really just no rules. Like my Harvestman stuff, it's all of the things that don't fit in the Harvest Band or the more mellow, for lack of a better word, the songwriter stuff. These aren't songs. These are more like sonic explorations. And sometimes they go into kind of a space rock psychedelic mode. Sometimes they can get a little dubby. Sometimes they're ambient. Sometimes they're noisy. It's just whatever the moment calls for. And then when a group of pieces feels like they belong together, then I gather them together and put it out. But it's very much my own That's me in my studio, turning on my equipment and seeing what happens. It's never written, it's never thought about, it's never intentionally composed. It's just inspired moments collected.

So I would assume that this basically answers itself for the fact that you never decide beforehand: "I'm gonna release a personal album or a Harvestman album". A collection of songs decide for themselves where they need to be.

Pretty much. I mean, for the solo stuff, I know when I'm writing solo stuff because it's going to have my voice. It's going to be based around singing. So most of the time I know when I'm writing a solo piece.

You're also writing poetry. And how do you decide when you're putting some words in the paper - Is this a poem? Should it stay like a poem without music around it? Or should this become a song one day?

Yeah, that's what I don't know. When I'm writing in my journal, when I have pen and paper and I'm writing words, it's usually just kind of following words and where they inspire me. And sometimes, I guess the best way to answer this is to go back to when I published my first poetry book. My entire adult life I wrote poetry, but I never had any plans to ever edit it or make it to what I thought was good or to release it publicly. I always just thought it was just for myself and for my own expression. And often, we know when it comes time, because the way I write music, whether it's in a rock band or whether it's in my solo stuff, I always write the music first. The melodic and the musical ideas come first, and then I see where the voice is going to fit in, where the voice is going to live on top of it.

When I had recorded the music for "No Wilderness Deep Enough", my previous record, I had composed that largely by accident. I didn't know I was writing a solo record. I was in Germany at my wife's parents' house, this land, this house site where her family has lived for over 500 years on this one spot. And I had horrible insomnia. I couldn't sleep. I had horrible jet lag. And rather than watch television or something, I just kind of woke up and I grabbed a keyboard and I was working on my computer using synthesizers. I didn't think I was doing anything. I just was killing time, not sleeping. When I got home from that trip and I opened up the files, I found them pretty interesting. I had written, by accident, a lot of piano-based pieces that were based on a really nice piano sound. I added some string synthesizers to it, and it was very melodic and very beautiful. I started adding analog synthesizers in my studio, like Moog and filtering stuff. Naturally, and it never felt like I was working, it just felt like I was playing and having, and exploring these sounds.

I had this entire record of beautiful, what I thought was ambient music, and I called my friend Randall, who was my engineer of the last couple records, and said, "Hey, I think I think I wrote this beautiful ambient work. I'd like to book a studio time with you and record a real piano, and I'd like to hire a cello player and a French horn player to add the melodic structures to support the keyboard ideas I came up with". He went away and listened to it, and he said, "I agree with you. We should book time in the studio, but you should also sing on it. You should not be so afraid - make it your next solo record." And I didn't believe him. I thought he was wrong. I thought my voice was too harsh, that I didn't need my gravelly voice on this beautiful music ruining it. But I respected his opinion enough to explore the idea.

By this time, it was winter. My wife had gone back to be with her family for the holidays. I was alone here with the dogs and I would light my fire in the morning that we were buried in snow outside and I would just take my cup of coffee. Instead of out in the studio in the barn, I just set a microphone up in the main room in the house. Every morning I'd get my coffee, light a fire, and I improvise vocal melodies. Within one week, I had all the lyrics and all the vocals finished. And I had to call him and tell him I agreed with him that he was right. But part of how I got all those words so fast was I went into my journals And I've always stolen lines from my own. It's a lot of times where I get lyrical ideas as I comb through things I've already written and I latch onto something. If something has to have the right, for words to live in a song, it has to sound right, regardless of what the words mean. It has to sound like it belongs in the music, you have to have the right number of syllables, the right vowel sounds, the right cadence.

The music also helps you interpret what you're hearing in the words and what you're feeling about what the words are saying. But on a poem, you don't have any context

It's something that I often discuss with Greek bands that used to sing in English. I don't know if you speak any of the languages, but the language is also very important because if it doesn't sound right on the music, it takes you off.

Right, and I think even the sounds of the words even if you don't know a language, like I don't speak any other languages, but I listen to a lot of music in other languages. Even though I don't understand the words, I feel like I get the emotional content and the resonance based on how they fit. This is a long way to your original question, but when I was going through that, I took this one line and the one line is, "We have the sea and we'll always have the sky". And I grabbed that and I put it in the song because it fit perfectly and it's exactly what I needed. But I looked back at the page of where I'd written the poetry and I went, Damn, that was actually a really good poem. And now I just ruined it because I took the best line. And now I ruined that poem.

And then I thought, well, who cares? Nobody sees your poems anyway. But that clicked something in my brain, like, well, why can't they both live? This line can live in this lyric as part of the song, and this line can live in this poem as a poem on a page, on a piece of paper. where the words are different and the meaning is different and the context is different and I'm stealing from myself, so I can go ahead and give myself permission to have this line in two places. That that triggered the inspiration that I should take my poetry more seriously and while I was finishing that record I was also waking up early in the morning and and diving deep into my poems and editing the ones I thought were the best and preparing them for my first poetry book.

It's interesting 'cause the poems, they don't have, music defines a lot of the emotional content of the words in lyrics and songs. You have the music to give it context, kind of like the way film and music work together. The music helps you interpret what you're seeing. The music also helps you interpret what you're hearing in the words and what you're feeling about what the words are saying. But on a poem, you don't have any context except for the words occupying that space on the paper. And it has to own that page and it has to give the reader a similar idea of what you were feeling when you put it down for it to resonate. They can interpret it, every human being can interpret a poem differently, but I think there's a certain common emotional content or theme that has to be present and it has to have a rhythm. People have to be able to read it in a way that has, it gives them some sort of hint to your internal rhythm. the poet's internal rhythm, otherwise they won't get it.

This was a pretty interesting insight on how you do your art. Back on what happened this year, you got the chance to present both of your works of Harvestman and the latest Steve Von Till album, as well as an art exhibition and a panel conversation in Roadburn Festival in the Netherlands. How was that experience? Which were your highlights there?

Sometimes you just have to take the opportunities that life presents you and I was given that much of an honor. First of all, I mean, the Roadburn folks are my friends. I really respect them and I love them and I love their festival. It's one of the most unique and incredible festivals in the world. And Walter and I have been friends for quite a while now and Becky too. To be chosen as an artist in residence and to be given the opportunity to fly all the way from the United States when I'm not on tour and to be able to present and bring musicians with me to present my new solo album and to pull off a Harvestman set, which I've never really done, at least not like that - and also to collaborate with my good friend Thomas in the art exhibition. It's something that he and I had dreamed about for years where I would soundtrack his paintings and the sound would be never repeating and to come from multiple, multiple directions, eight different sources looping and but never repeating so that any time you walk into that gallery, it will be similar, but always different.

To be able to have some deep conversations, to be able to get the opportunity to read poetry at the art opening, to be able to have a talk with Thomas at the gallery, to be able to have the talk with Jose and Thomas on the festival site on the Sunday, all of it was just really a dream come true, and like I said, a real great honor. I really do believe I make art for art's sake, and I think I just am lucky enough to be able to tap into something that exists out there in the universe, that it's not necessarily human beings - we aren't necessarily solely responsible for the art. It's just, sometimes we're lucky enough to have it flow through us. And so to be celebrated like that by others was very emotional for me, to have my kind of life's work celebrated and honored like that was.

Yeah, I was there, so I totally understand the vibe of the whole situation, both on sets and outside them. And what was your favorite thing that you saw from another artist there?

I had a plan of things I wanted to see, because when you're playing a festival, honestly, even if there's something you really want to see, sometimes you don't have the headspace, especially if it's a day you're performing, it's really hard to focus. I'm extremely nervous, I'm not a natural performer. I do it because I feel like I have to, but I'm totally a nervous wreck every time I get in front of people. I did wanna see The Bug, so we made sure we stopped our rehearsals that night in time to get there, he's one of my favorite artists of the last several years. I luckily got to watch Oxn because we played the same stage on the same day. I'm a huge Lankum fan, I've never seen Lankum, I will see them in October, but I really wanted to see both their side projects. I did get to see One Leg, One Eye, which was a big one for me. And my friend Aaron Turner and his band Sumac, they did the set with Moor Mother, which I really enjoyed. Oh, and Big Brave.

Some festivals, as you said, are pretty amazing places. One thing that I did not know exist in the world, and sometimes it's hard to get the information back here in Europe, was one thing that you started as storytelling in Roadburn, which had to do with the Firekeeper Alliance and the Fire in the Mountains Festival back in the USA. I want you to tell me a few words about how you got involved with Firekeeper Alliance, what that is. And since back in Roadburn, the FITM festival didn't happen yet, what was the actual experience when the festival took place in the summer?

Fire in the Mountains is a festival that had happened previously in Wyoming. I first learned about it in 2022 when I was asked to perform there. I had never heard of it either. It was quite grassroots and more local to people out there in the mountain states. I'm not that far away, but it just wasn't on my radar. It was all small and DIY, no corporate sponsorship, and in America, of course, there's no such thing as government money for the arts, so this was all totally self-run. I guess the year I played was when they were trying to grow it a little bit. They brought Enslaved over from Norway and they brought Yob out as a headliner. I headlined the first night as a kind of more mellow music night with my solo project. And a lot of interesting artists in a beautiful landscape. It was in the Grand Teton Mountains out on a ranch. This wasn't out in a regular festival ground, not near any sort of town. It was near a national park, not near a big city.

I've been to cool music festivals with great bills before. I've been to Roadburn many times. I've been to Supersonic. I've been to great festivals with great lineups and independent music and DIY mentality. But what really blew me away about this one, especially for the United States, was they had representation from indigenous people, the native peoples of the Americas. They had elders talking about landscape and music, the connection between spirituality, there's surviving hundreds of years of settler colonialism and genocide. They also had a very eco-conscious mentality of leave the land better than you found it. Leave No Trace. Everyone was super respectful, everyone was going out on the river and taking hikes and going into the forest, and there was ethnobotany walks talking about, so it's things that you would never experience at a heavy music festival. It was quite, mind-blowing.

But what really blew me away about this one, especially for the United States, was they had representation from indigenous people, the native peoples of the Americas

I told them I thought that was really unique, I was really impressed by the spirit of their thing, and would they please keep me involved. They lost their spot for a couple of years, and a guy named Charlie Speicher, who now I consider a brother, he was at that same festival. When they lost their spot in Wyoming because the rich people in Jackson Hole didn't want them to come back, He, Charlie, is the head guy at an alternative high school on the Blackfeet Nation, the Blackfeet Reservation land east of Glacier National Park in Montana. He had these things click in his head that he thought that he could talk to the tribal council of the Blackfeet Nation and talk to Fire in the Mountains and maybe have that festival there.

Part of what we talked about is using heavy music as a catharsis, using heavy music as a wellness practice, using heavy music as a healing force. We look the darkness right in the eye and we don't shy away from it in this music. I've always thought, the music helps us get through tough times, the dark times in our mind. Helps us find our community. So Charlie took those ideas and worked with other awesome people that he's tight with there - Blackfeet language keepers, keepers of their traditional language, teachers, mental health professionals, all kind of working together. They've decided to form the Fire Keeper Alliance to be the bridge between Fire in the Mountains Festival and the Blackfeet Nation and the heavy music community. Through a lot of heavy duty work on everybody's part out there in Montana and on the ground, the tribe agreed to it on the basis that it would be used to help the youth. And that was Charlie's plan all along, because all these folks that work in the schools, they know - the youth junior high and high school age have been suffering a suicide epidemic of devastating proportions. The numbers are beyond what seems reasonable in any community.

All these folks that work in the schools, they know - the youth junior high and high school age have been suffering a suicide epidemic of devastating proportions. The numbers are beyond what seems reasonable in any community

This is something that the folks, the fire keepers who are living there in the Blackfeet Nation had already been working on in their community because they're working in the schools, they're working with these kids. They'd already been brainstorming ways to make mental health practices available, like services applicable to native people, to indigenous folks. Most of our suicide prevention assessment and postvention coping after a loss practices come from the modern Western society, which one, I would argue they don't work in modern Western society either, that they need to be rethought and reinvented. But they definitely are not applicable to indigenous communities, because they tend to pathologize, "what's wrong with you?" as opposed to what's, "Charlie would say, what's strong with you? What's, what's right? What strengths do you bring?" Have mental health be based on their own traditions, based on their own language, based on their traditional healing practices, based on their idea of community.

In the West, we're all isolated. Every family has been isolated to its own unit and every individual isolated into its own individual. And it's your job to get help for yourself. You have to do the work. Something wrong with YOU. And that's not the way they think, or the way they view themselves in the universe. They wanted to indigenize these mental health practices, make them available, reconnect them with their ancestral traditions. They still live in their traditional lands, and so reconnecting with the outdoors and with their native landscapes, with their ceremonies, with their language, but also, while embracing what my friends in the Firekeeper linesare bringing on the table. They’re metal fans, heavy music fans, taking what they learned in this intense music getting them through hard times, using that as an additional wellness practice and finding one, self-expression, as I already said - staring darkness in the eye with art and music and words and poetry, finding community. The other, people that maybe feel that they don't fit in, and they're looking for somewhere where they fit in.

Heavy music has always been that for me. I've always found my community through music. Through the outsiders, the weirdos, we always found ourselves. When I was a teenager through punk, through the punk rock world. And later on, as it evolves beyond category names, just people that are into independent, intense, emotional self-expression. It's a community. We thought we could also tap this community. And they brought me in as they were forming, to join the board of directors as kind of a liaison to the heavy metal world. They were kind of honoring me as a lifer in this world and I guess coming from Neurosis, maybe we were one of the first bands to openly talk about using music as a catharsis and as an emotional purge - as a way to look the dark stuff right in the eye and to purge it so that we can live without it.

I think Enemy of the Sun changed a lot of stuff in music based on what you just said. I don't know, it's a very sentimental record for me.

Yeah, for a lot of us. Even as somebody on the inside creating it, it changed things for us as well. So it all worked out, and in July, they had the Fire in the Mountains folks doing what they know how to do, organizing the logistics of a festival, the stages, the sound, the infrastructure, while working partnership with the Blackfeet tribe, hiring the local people that understand that landscape. They're in this beautiful campground on the shores of Two Medicine Lake. We had 3,000 people camping in this incredible music festival with a great lineup, everything from Chelsea Wolf and Emma Ruth Rundle to Wardruna as a headliner, Blood Incantation, myself. Converge was chosen as the Firekeeper band because of their lyrics and lyrical content openly confronting suicidality.

I should also mention that one other aspect of it is to stop making feeling suicidal a problem. To destigmatize suicidality, to destigmatize mental health, to destigmatize feeling low, but to support each other in confronting when you don't feel all right. What's not normal is following through with the suicide. You had this external community coming to these people's traditional land. I might also add that it's alcohol free out of respect for the indigenous people and the complicated relationship with alcohol on reservations. And I would say that that also proved for other people to be enlightening because again, the music was part of it. There's a great lineup in this beautiful landscape where you had indigenous people and the local community came out with these thousands of people from outside coming. Indigenous and non-indegenous people in this country, it's a complicated relationship because you have the descendants of settlers and colonialism and genocide, those of us that have inherited that role and the folks that have been victims or suffered it. I don't wanna say they're victims, but that have had to suffer and endure and survive that for the last few hundreds of years. Coming together in a rare moment of real unity and real togetherness and real sense of purpose, because it was openly addressing that idea of this is to help our youth in this community deal with this suicide epidemic.

Indigenous and non-indegenous people in this country, it's a complicated relationship because you have the descendants of settlers and colonialism and genocide, those of us that have inherited that role and the folks that have been victims or suffered it

There were classes that had happened in the high schools for the semester before, called the Heavy Music Symposium, where the teachers had taught kids in schools the history of hardcore punk, heavy music, and extreme music, and gotten them involved in making stuff and making noise and creating the artwork. They even helped design a Wardruna shirt and an Inter Arma shirt and a Old Man's Child shirt, then donatethat money of the sales of those shirts was donated back to the Firekeeper Alliance organization to help us do our work, providing a shield for the Blackfeet community in this against suicide, suicidal distress.

Back to what inspired me about Fire in the Mountains in the first place, there was the programming outside of the music. First of all, the Thursday night was the Blackfeet were hosting it in their traditional way, where they had their traditional songs and their traditional dance and their traditional ways of welcoming people in this area that was actually a place where they were used to, in their history, welcome other tribes in for special events. In this case, it was people from all over the world, the Wardruna folks and all the people that came from Norway to bring their perspective and their energy to this event. They celebrated their culture and they were able to put it on, to share it with all of us that were from outside, and it was very beautiful. It was very, you could just feel the heart in every aspect of the festival. Literally every single day, people were brought to tears of joy, of grief, of sadness, of transcendence. It was emotionally heavy. It was like a mass healing event.

You can probably tell by just my tone of voice, how incredible it was. I've been a part of some amazing musical events in my life. And this was a whole other level. There were carryovers of yoga. There were musicians talking about the power of music as medicine. But all of it now was shifted to a Blackfeet oriented perspective of connection to the land, surviving trauma of hundreds of years of settler colonialism, missing and murdered indigenous persons, because that's a massive issue in Indian country here in America. Talking directly about suicide, talking about healing trauma in the body through yoga or land-based connectedness, but also having people share their ideas from the Nordic countries, of their traditional songs and ways that it helps them.

It's hard for me to summarize but it was 20-something workshops and these started at eight in the morning and went till two in the afternoon. Since it was alcohol-free every single workshop was packed with people. Bright-eyed, clear-headed, clear-hearted. Ready to take in this information. There was ethnobotany walks with native experts in the landscape, taking people on walks and talking to them about the native plants and their traditional uses and their traditional stories. There were traditional songs, traditional storytelling. It was so incredibly deep on so many levels that it really is hard to put into any sort of summary. But it left everybody there feeling like they were part of something historical, something needed, something epic, something emotional, something transcendent, and perhaps the beginning of a consciousness shift.

Oh God, this was deep.

In this time, in this world, we need that. In this world right now, when you turn on the media and you look at everything going on, how doomed this country seems, and the things going on in other parts of the world that are so incredibly horrible, we need a consciousness shift. And this was an example of how that's possible.

It's truly an inspiration about what you can do because, maybe this specific form of how this festival took place there, cannot happen in all areas of the world exactly as it is, since the situation between Native Americans and USA citizens that come from people who overtook their lands as, settlers back then, it's a very specific relationship that I believe if you're not from the USA, you cannot completely understand how it is. But I believe that these type of ideas, if executed well, they can find ways to make bridges between populations that are outcasted anywhere in the world.

Right, and how we can view this heavy, intense music as a wellness practice, as a healing form of art, not just some scary thing that people think when I was growing up. You'd see stuff on TV and in the news where people would try to accuse our music of causing harm. And we always knew that wasn't true. Now we're actually getting validation from the other folks in the Firekeeper Alliance, for example, who are trained clinical mental health professionals leading the way.

Yeah, that's true. I think it helps a lot the fact that towards the past few years, punk, hardcore and heavy metal music are more open to minorities, be part of the bands themselves, be part of the scene all over. I mean, there are more examples of any type of person that doesn't fit the norm nowadays, from women to black people to indigenous people to trans people. It's open for much, much more people nowadays. And it's really amazing for us that we see it happening from being kind of a closed place to now be more welcoming and using this power of healing inside it.

I agree, yeah. when I was a young man and the heavy metal world kind of seemed like closed. Once I discovered punk rock I thought sometimes it could be more. Of course, it was a different time. In the mid '80s, the DIY punk scene felt very open-minded in that it was often challenging social issues, or at least certain aspects of it. There was also always the meatheads. But it seemed more open, but heavy metal seemed particularly kind of not open to that, like back then in the '80s. To see the scene change and grow and the genres to kind of fall away and to become this more fluid heavy music world, it has become probably the most inclusive scene that's out there. which I would have never predicted when I was a young man, that it would become so inclusive. And it's a beautiful thing.

I'm 32 now, and even when I was young, back in my 14, 15 years old, I was like, you'd have to fight being just a woman, to not have any other non-privileged aspects of your personality. You had to fight to consider yourself, a person that's valid in the scene. Only 15 years ago, and today it's something totally different. Which brings me to the question of, wwhether you have observed some new artists or bands that are fairly recently introduced in the scene that you believe they have something very unique to offer?

Who? There's so many. Yeah, as much as it would be easy for me to become jaded, being an old guy and liking a lot of older stuff, I do see stuff that are good. My sense of time is different because to me a decade now doesn't seem that long. But I mentioned Big Brave, I think, and as far as heavy music goes there, one, having women involved and not having that kind of traditional posturing that heavy bands do of looking tough. They just seem to cast all of that aside. They are just really into making this very unique, heavy music that doesn't have any of the tropes of heavy metal or of punk. It really is kind of their own unique take on making something emotionally heavy. It's beautiful and melodic, but also dissonant and crushingly heavy and very unique. So I really like how they're, especially as time goes on, they become more and more to themselves and more and more unique. Their music gets further away from anything you can categorize.

I love Lankum and their side projects, how they're taking something which could be very traditional and conservative, like Irish folk music and blowing it out into something darker and crazier and heavier and vital and alive right now. Which is also what I've loved about Wardruna. Now they're huge and have gotten very popular in the last decade. But I find it very encouraging because you would have never thought that heavy music would become the most inclusive music scene, you would have never thought that there's a band that sings in their native Nordic tongue on ancient instruments. A kind of a new music created from ancient ideas, singing about arcane old symbols and concepts and back from an animist time, a time before the modern world, not doing any sort of recreation or historical stuff, but making something new with these old roots. You would have never thought that they could become so popular that they'd be playing Pompeii and big theaters across the United States when they're not singing in English.

They were playing over here in the center of Athens that there is a very popular Greek ancient theater in the middle of the city that's called Herodion and it was exactly what you're describing. People playing in Nordic with their instruments in a Greek ancient theater but with people from today watching them in the new version of Athens it was surreal.

It was so the fact that they connect so deeply with so many people all around the world, it is incredible. They've been a constant inspiration. And then, there's also just grassroots, gnarly, filthy bands that I love, like Deaf Kids from Brazil, also do kind of a unique take on their own heavy music that's very informed by where they come from and their musical traditions in Brazil. And bands that we've put out on Neurot recordings, like Great Falls and Kowloon Walled City and X Everything.

Kowloon Walled City, I think they're getting back. I think somewhere they're gonna release some new music.

I think they're working on something. I love those bands pushing that envelope as well. I always hope that things will keep coming around that kind of blow my mind. There's also a lot of bands that want to play an old style and I understand. But it's neat when people take those inspirations and make something new out of it that doesn't feel like wearing a costume, it feels genuine and authentic. I think there's a lot of that, probably more than I know, because there's probably young people out there making their own version of punk rock that I'm completely unaware of, because it's in a different scene that only the young people care about, at least I hope so.

I stole that idea of "pay what you want" on Bandcamp from Jeremy at Temporary Residence Records

Always something is cooking. I try to stay as informed as I can, but there's too much good music all around the world and that makes me happy, but also anxious to find out all of it. You mentioned Neurot Recordings and I was also going to ask you about that. Among all of the many things that you do, you have also a label that is Neurot Recordings. Most of people following your work know about it, releasing your work and artists that you trust, I imagine. And you are following a policy. It was even from the pandemic era that you decided each week to have an album that is out of Neurot Recordings for "pay what you want" price through Bandcamp. How did you decide to go there?

I stole that idea from Jeremy at Temporary Residence Records. They are a great record label based in the East Coast, which we've shared a couple of bands. They put a lot of great music. And they're a very successful label. But they started doing that during the pandemic. And I love the idea so much. I emailed Jeremy. I said, "can I just steal your idea? It's too good". And so we put our own kind of vibe to the idea. If you view music as something that's going to help you, if you view music as a healing thing, then sometimes you need to make the medicine free to people. If music is medicine, then sometimes it should just be free because people need it. And so that's the primary motivation.

The second one is, we have a deep catalog and maybe people can't afford to try it all, but we want them to have a chance anyway. It is available for free if you want, but it's also pay what you can. If somebody else is doing well and they really love something that they downloaded for free, then they might wanna go back and put $20 towards that artist, or overpay for the record to support it. We’ve seen a good response from that. The people that need it, take it. People that are curious, check it out. So it's kind of self-promotion as well as doing something nice. It seems to have a payback on multiple levels. So thank you, Jeremy, from Temporary Residents for letting us steal that idea.

You've been also a person that has lived through the very distinct two different eras of music nowadays. Before the vast expansion of the Internet and social media and how we know them today, the way that we would listen and find out music was kind of different. So how does one that has been around in the music industry for a while copes and learns the new ways? Do you have to do that? Do you adjust yourself in some ways? Because today, you have to put your music out there through social media outlets, through other labels. I don't know exactly how one adapts, because my generation was-- We barely reached that era where we would buy a few CDs each month because we couldn't find them in the internet. And then the internet came to our houses and we could find any music that we wanted to. Very slowly, but we could.

It's been interesting. Admitting that change is the only constant and if you want to remain relevant and involved, you have no choice but to go with the flow, especially if you know you are an artist and you have your own record label. Personally, I still love, as a consumer, physical media. I really love putting on vinyl records still. I mean, I have a record player right in there inside the house and I have one downstairs and I have one in the office. I have records all over the place. I haven't got rid of my CDs, but they don't get a lot of love. I stream music because it's convenient. In today's day, when you have a Bluetooth connection, you're gonna stream it. But I still try to support the artists that I love by buying something physical, in most cases, vinyl. As far as interacting I do feel nostalgic for the days when you were saying, it was hard to even find records of bands from Europe, for example, in the mid-80s.

And the scene there was huge back in the day.

You wouldn't have those records, they wouldn't be here. So I was part of a tape trading community where we would buy cassettes and we would make lists of all of the things that we had and we would Fold up the list, put it in an envelope and send it to somebody in a different country. They would send us their list and we would say, okay, the tape has 90 minutes. Choose what 90 minutes of stuff you want and this is what 90 minutes of stuff I want. We would just trade the tapes back and forth and turn each other on to even just demo tapes of bands that couldn't even put out records yet.

Or rare records that we couldn't get, we would send cash in an envelope and mail it and hope you got a record back. I do miss fanzine culture of people making their own magazines of their local scenes and trading it with people in other parts of the country or other parts of the world talking about their scenes. What I do love about that time and what makes me nostalgic, I think in some ways it might be coming back with people embracing their own cultures more, but I liked that German bands sang in German, Polish bands sang in Polish, Scandinavian bands sang in their own languages. Then, there seemed to be something that happened in the '90s where everybody started singing in English, everybody started wearing Levi jeans and wearing Vans shoes, and the whole world started to feel like it was getting the same. I liked it when punk rockers wore whatever weird clothes they decided. But the past is the past and you can't live there.

When we were first starting touring, there weren't even clubs in America where we could play most of the time. It was a lot of house shows and basement concerts and people renting spaces and putting on DIY shows, whereas now there's kind of an international club scene where bands like this can play all over the world, which is a new phenomenon. The internet coming, that's huge pluses and minuses. One, it democratized people's access. You can find anything you want now. So the thrill of the chase is gone. If somebody tells you about something, you can find it in 30 seconds. At the same time, it also means that everything's available, so the sea is endless. To be able to find something specific becomes more challenging, or for a young band to hope that anybody pays attention to them in this vast sea of people recording at home and uploading onto the internet at home is crazy. It used to take a lot more willpower to be able to figure out how to record, to figure out how to make a record, to figure out how to get out of your garage and out into a show I try to just always go with the flow and adapt with it. It's definitely harder to run a record label in this era of streaming and vinyl because vinyl is expensive and you don't sell a ton of it and most people get the music for free. It makes it harder to survive.

You've got the gig and you've got the flyer. Everything that's not a gig is a flyer

But still people are buying vinyl, despite of the fact that streaming is so vastly available.

Yeah, but vinyl's expensive to make. The profit margin on CDs was you invest $2 and you get seven back. The profit margin on an LP is you invest 8 and you get 11 back. Then you also still have to advertise and you still have to hire PR people. So it's definitely tougher. I got dragged into social media kind of kicking and screaming that I didn't really want to do it. It didn't seem very inspiring to me to be a part of these kind of social media platforms. When I was 15, I spent a lot of time going to the copy store with a Sharpie and scissors and a glue stick to make a flyer and spend a couple of hours making a flyer at the copy store, and then driving all around town putting them up on the telephone poles, for the concert.

And so now I try to take like Mike the Minutemen word: he says everything comes down to two things. You've got the gig and you've got the flyer. Everything that's not a gig is a flyer. A record, it's a flyer. So I try to take that idea and think, okay, social media is the flyer. It's the new telephone pole. I try to look at Facebook and Instagram as a telephone pole, a place where I'm putting up a flyer to get the ideas I want to get across to people where someone will see them. A lot more people will see something if you build up a following on social media than if I hang up a flyer at my local coffee store nowadays.

It's interesting because you don't want to get caught in that kind of disease of social media, thinking that that's where your sense of value or self-worth comes from

You have your specific audience, it's not putting in at some random location and some people might be interested, some might be afraid, some might be, annoyed.

It's interesting because you don't want to get caught in that kind of disease of social media, thinking that that's where your sense of value or self-worth comes from. A lot of people are sitting there and hoping that people click on their likes. For me, it's promoting music. So yeah, I want to sell records. I want people to come to the show and I feel like it's a lot of work to try to get every single person that might want to show up to that show. It takes a lot of work to let them know that it's there and that I would appreciate them coming. It's not a given. Being part of a community without getting sucked into the sickness of the Internet and social media is hard. It's a weird line to walk on.

On another topic,the past few years, we have seen some collaborative albums going on in our scene with pretty extensive musical outlets, such as the collaboration between Converge and Chelsea Wolfe, or Julie Christmas with Cult of Luna or Emma Ruth Randle with Thou. And many bands the past few years do collaborative albums. You were a pioneer of that, if we recall back in the day, the Neurosis - Jarboe album collaboration. Would you consider doing something like that, and who would you choose?

I did- on the Harvestman stuff, I was able to collaborate with some folks and bring in some other musicians, my friend Dave French, who's plays in my solo group and also drums for Yob. We've been collaborating, so that's been nice for me to actually play with some other musicians. I was asked to do a collaboration also. There's a Hungarian band called Vágtázó Halottkémek (Galloping Corners) that's been around since the late '70s, really heroes of mine, kind of psychedelic shaman punk. I did a reinterpretation of one of their songs, which was a collaboration in some ways as well. And I sang on a Sangre de Muerdango from Galicia song. I put some vocals on Wolves in the Throne Room. I did a reinterpretation of a Lustmord record for a record that he did where other people interpreted his songs. I also sang on a Converge record a long time ago before they did the Chelsea Wolf one. It's been something I've always been open to.

I had the Bug remix a track of mine on the Harvestman record, which was a great chance to collaborate. I've got some things right now where I'm going to ask some people to collaborate with my music as well, but I'm not ready to talk about that yet. First and foremost, the other human beings and I have to get along personally, like we have to feel a kinship, there has to be a relationship and feel that our different musical perspectives would have something to offer each other, you know?

Yes, and I believe this spirit of togetherness is a very good place to stop.

Okay. Well, thank you so much for your thoughtful questions and your time. I appreciate it!