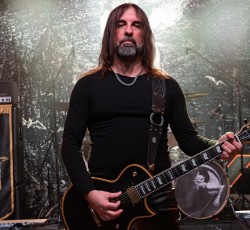

Rock Culture #26: Few can discuss a music subgenre like Dayal Patterson

"I wanted to set the record straight and tell a broader story about black metal, because the history was being increasingly distorted"

Μπορείτε να βρείτε την ελληνική εκδοχή της συνέντευξης εδώ.

Music history very often intersects with its myths. For a typical example, there is black metal. Few musical subgenres have such an imprint on pop culture, prompting people to form an opinion about them before they've even heard a note. Furthermore, very few musical genres have been the subject of study, not only scientific and journalistic, but also artistic. Black metal’s history, is more or less well known, or maybe not. Among the multitude of works on this particular sub-culture, "Black Metal: Evolution Of The Cult" stands its own ground.

The book, edited by eminent journalist Dayal Patterson, was originally published in 2013, and has since been a landmark work in dealing with the genre. With a series of interviews with the majority of the key-figures to the birth, formation, and evolution of the scene on a global scale, the book covered a lot of ground in a history with many twists and turns. But Patterson, also responsible for the recent biography of Rotting Christ, was not happy. Through his publishing house Cult Never Dies, "Black Metal: Evolution of the Cult - The Restored, Expanded & Definitive Edition" is being released in a few days. As can be seen, the story according to the publisher was not fully told.

Being a website that covers this music genre extensively, there couldn't be a better occasion for an extended chat with Dayal. The following interview focuses on this new, massive and rich work, its differences from the original, as well as the goals of the publishing house. Quickly though, it will depart from them, and will turn into a frank discussion around a series of topics about black metal in general, its peculiarities, philosophy and aesthetics, as well as the historical greek scene in particular. Personally speaking, having a deep respect for Patterson's work, I found the new, revised edition of "Evolution Of The Cult" vastly superior to the original as a book that illuminates several (but not all) aspects of the scene, while also sparking the curiosity of the readership to raise questions and decide for themselves how they perceive such a multifaceted idiom. In addition, I believe that what you are about to read below is an essential introduction to this special artistic world.

"Black Metal: Evolution of the Cult - The Restored, Expanded & Definitive Edition" will be available via the following links:

Cult Never Dies Main Store

Cult Never Dies Europe

Decibel Books

Greetings Dayal, my name is Apostolis and I welcome you to Rocking.gr! Where does this interview find you?

Hello Apostolis! I am sitting in the office in the Autumnal English countryside with a cup of coffee!

You are about to release “Black Metal: Evolution of the Cult - The Restored, Expanded & Definitive Edition”. What urged you to revisit your seminal work after 10 years?

I’ve wanted to revise this book for all of those 10 years to be honest. The original book was released by a publisher who gave me a maximum wordcount of about 200,000 words and the story I wanted to tell needed a lot more than that. For that reason, a lot of content was excluded from the original and so I always had it in mind that I would want to buy back the rights to the book if I could and completely recreate the book I had in mind via my own publishing house, Cult Never Dies, without any external interference. It took a decade to get there but now it is finally available with 140,000 more words than the original and 350 more images, plus hard covers.

The release also marks the anniversary of the Cult Never Dies publishing house. How difficult was it for you to start this company, and was it ever a point in those years that you felt that you exceeded your expectations?

Cult Never Dies started in the most humble and D.I.Y. fashion, basically being a small mail order selling just two books and a single shirt design, and being run by myself from my flat around working in a normal job. There was no start-up money or loans involved, each new release was funded by the sales of previous items, and so initially we didn’t sell many different titles. I went full-time with the company in 2016 and employed staff the following year and we’ve steadily and organically grown from there.

Today we’ve released some 30 publications, 100 items of official merchandise and 8 records, plus we have two mail-order stores, the main one distributing about 700 items at any one time including books, fanzines, shirts, CDs and vinyl. In that sense, it is always exceeding my expectations, because I didn’t look very far ahead or predict how it would grow - I just wanted an outlet for my creations.

That was always the aim really, to set the record straight and tell a broader story about black metal

Back in its initial release, “Evolution of The Cult” was treated by the greater black metal community, be it the fans, journalists, or musicians of course, as an important testament to the history of the genre. Apart from the “historic” value, what did you want to succeed with this work?

That was always the aim really, to set the record straight and tell a broader story about black metal, because the history was being increasingly distorted by outsiders who were reducing black metal to being about Norway from 1991 to 1993. With Evolution I always wanted to show that black metal had begun in the 1980s and that there were a lot of other countries involved with the creation and evolution of the genre, be it Brazil, Greece, Sweden. I also wanted to allow the musicians to tell their own stories and to include interviews with less obvious bands, such as Master’s Hammer, VON, Beherit, Rotting Christ, Hellhammer/Celtic Frost, Thorns, and Blasphemy, as well as the more obvious likes of Darkthrone, Mayhem and so on.

Black metal is comprised of individuals whose motivations go far beyond simply making enjoyable music

"Black Metal: Evolution Of The Cult - The Restored, Expanded & Definitive Edition", holds with quite ease its ground among many important books about the metal scene and subculture. Why do you believe though, that it would interest an individual that does not listen to this music?

The book is so expansive that I think it can be enjoyed by someone new to the genre or by those who have been in the scene for many years – Roy of the long-running Imhotep fanzine commented that he learnt many new things despite being active since the early days of Bathory, so that is very encouraging.

I also believe that the book is definitely of potential interest to people who don’t currently listen to the music, because black metal, and by extension the book, is comprised of individuals whose motivations go far beyond simply making enjoyable music. I’m not sure that you could make a book like this for death metal, as much as I enjoy listening to that, because there is such a depth of spiritual, ideological, artistic and philosophical ambition within black metal, and that’s explored within the book.

The new edition, contains almost 1/3 of new material. Has black metal changed so much in these 10 years? How do you view the scene today?

To be honest, most of the new content in the book has nothing to do with the last ten years of black metal, although there are a couple of chapters addressing that. Primarily, the book is concerned with black metal’s most formative years, between the early 1980s and the early 2010s, although I do follow each of the main bands featured to the current era – ie. there’s a chapter on Profanatica, and we talk a lot about the early 90s, but also bring things up to date by talking about the reformation and recent tour stories and releases.

But the majority of the new content was used to expand upon things already touched upon in the original. For example, when discussing depressive black metal, I only really focussed on Shining in the first book because of the lack of space, but the new version also features interviews with Forgotten Tomb, Bethlehem, Silencer, Forgotten Woods and so on. Likewise, there are whole chapters on bands that were only mentioned in the first book, such as Necromantia, Mystifier, Immortal, Impaled Nazarene, Absu, Winterfylleth, Deviser, Hecate Enthroned, Vinterland, Satyricon, Arcturus, Deathspell Omega and more.

There are chapters and pre-existing interviews that are now expanded. How did you decide, in the original version to leave some parts outside the book? Do you think that their inclusion now, changes any of the narratives of the book?

The new book gives a broader and much more accurate impression of the history of black metal essentially. With the original book I simply had to cancel and stop working on certain chapters because I’d already reached the maximum word count and the people I was working with wanted to press on and release the book. But it’s not just about the new chapters in the book, it’s as much about the additions to the already existing chapters. I think one obvious example would be the parts about the Helvete store and surrounding scene, because more people involved in that gave interviews and so there is a much more realistic understanding of how that really was. I also had space to expand pre-existing chapters on bands such as Thorns, Burzum, Rotting Christ, Sigh and Mayhem. The devil is in the detail with a subject like this, and having more words to play with meant a lot more fascinating details could be included.

Greece is a very important country in the history of black metal, and I’ve always felt that there is a real sense of magic about those early years

One of the scenes that earn a more extensive treatment is the greek black metal scene. It is interesting that many interviewees speak about "competition" apart from collaboration. How would you explain that, taking into account the testimonials of many greek artists in your book?

Greece is a very important country in the history of black metal, and I’ve always felt - and even more so after writing the Rotting Christ book with Sakis - that there is a real sense of magic about those early years and more to tell. But yes, a lot of Greek black metal musicians have spoken about there being a competitiveness between bands, which is something that I haven’t found so much in other scenes. This, as people like Necromantia’s Magus and Agatus’ The Dark suggest, may be the flip side of the apparent unity that was present in the scene during the glory years of Storm Studios, Go Underground and so on.

What is the element that fascinated you more, when you were unraveling the creation and expansion of the greek scene?

The Greek scene has a rich history that really conjures my imagination, just as much as hearing about the Helvete/Norwegian stories of the early 1990s does. I think there was an infrastructure and sense of community in Greece that can only really be compared to Norway and Sweden at that time, in the sense that so many musicians, label owners, fanzine writers, artists, promoters and so on were collaborating creatively and socialising. Actually I think Athens and Greece are fascinating generally, quite aside from music, and revisiting Exarchia square or the now abandoned sites of Go Underground, Metal Era or Storm Studios, this was very meaningful to me, and hopefully that comes across in the book.

You are also the author of "Non Serviam: The Official Story Of Rotting Christ", so your experience with the greek scene is more intermediate. Rotting Christ, are considered, not only the household band of the aforementioned local black metal scene, but more of greek metal in general. How do you explain that in a country like Greece, an extreme music genre acted as a lighthouse for a broader spectrum of artists, despite its subcultural nature?

There are probably a huge number of sociological and historical factors that explain why certain places become disproportionally important within the context of a certain type of music – Norway with black metal, the UK with punk, Florida with death metal, Finland with folk metal and so on - but my personal theory is that if you when a strong focal point is created, then people will inspire each other to create something interconnected. It is no coincidence that Norway, the country with the first proper black metal record store, spawned so many superb and interconnected bands playing that genre of music. Likewise, Greece, and in particular Athens, was unusual because it had so many record stores selling metal, a couple of functioning record labels, and a studio owned by the biggest band in the scene. Just having this sort of infrastructure and social dynamic is enough to spark many people into productivity and creativity that they might otherwise have not engaged in and so puts that country on the map.

I think when you inject politics into black metal it generally becomes something else

One of the chapters that grabbed my interest in both versions of the book, was the pages about the relationship between black metal and national socialism/fascism. As interviews and articles, they were really interesting. In the last years, I’ve noticed a strong wave of anti-fascist black metal bands, often using the tag “red anarchist black metal (RABM)”. How do you view the evolution of this genre, if you are familiar with it?

RABM and NSBM ("National Socialist Black Metal") have a similar relationship with the wider black metal scene in that they are considered by many to be too political to be considered black metal and so end up becoming quite self-contained movements, with their own audience, some way away from the rest of the scene. I think it’s quite acceptable to have left wing ideals within black metal, after all a wide range of bands always have had that, be it Rotting Christ, Mystifier, members of Carpathian Forest, Fen etc etc, but I think when you inject politics into black metal it generally becomes something else. The NSBM bands that have crossed over into the broader black metal scene are generally the bigger and better groups, most of whom toned down their political content. The RABM movement is still very new and perhaps the same will happen given time, but to date, no bands from that scene have genuinely crossed over into black metal as a whole and their audience tends to be mainly people from a punk background in my experience.

We treat artists differently for reasons of taste not morality, because we like to relate to them on some level

The vast majority of the interviewees have taken the thesis of "separating the art from the artist". Still, and this is a riddle for myself, how viable and real is this separation, when the musicians are conducting interviews talking about the artistic and creative process, or when the support of fans is mostly financial?

Well the financial issue is a very relevant one I think. One can enjoy a band’s music but you might choose not to buy their records, or attend their shows, or work with them, if you disagree with their beliefs or message. As far as enjoying or experiencing music or art, then I think one should separate art from artist, to the extent that I can enjoy the specific performance of a musician that I might not like as a human being. I think everyone does that actually, but we each choose where we draw that line. I also wonder if people, especially in the internet age, place too much emphasis on the beliefs of artists. Why not ask for the political beliefs of your workmates, or employer, or the baker or greengrocer you buy your food from, if it’s so important to agree with people before dealing with them financially?

If people were really worried about supporting people with different beliefs, they would probably avoid major banking institutions, change where they shopped for their groceries and so on. We treat artists differently for reasons of taste not morality, because we like to relate to them on some level. But that’s an issue of taste not ethics.

The fact that people want to use the term and the associations, but distance themselves from those things is extremely problematic

You dedicate an important part of the book to express your opinions on what is and is not black metal, and I admired your conclusion on the topic. The parts with post-black metal and blackgaze were intriguing. Personally, even though I understand your thesis, I personally believe that every self-definition, is acceptable, since black metal was since its beginning ever expanding. How significant do you think that this issue is today, taking into account the current state of the genre?

If every definition is acceptable then I think we must conclude that it’s better to never use definitions at all, because otherwise I can claim that Limp Bizkit or The Beatles is black metal and no one can tell me otherwise. As long as we use classifications and genre terms then we have to define what those classifications and genre terms mean, and what they include and don’t include. Since the term ‘black metal’ has had a broadly accepted meaning - or set of meanings - for about 30 years within the scene, I think it is problematic that people from outside of the scene now attempt to redefine it to fit their own tastes. To that end I would say that the last few years has seen a cultural appropriation of black metal, and although there are bigger problems in the world, it is natural to recognise and comment upon this.

The term ‘black metal’ is used by bands, labels, academic and PR folk because it carries a huge weight, a weight based on 40 years of history, ideology and art. It is based upon anti-Christianity, upon misanthropy, upon underground ethics and extreme and groundbreaking music, among other things. The fact that people want to use the term and the associations, but distance themselves from those things is extremely problematic. Deafheaven, for example, say themselves that they are not black metal, but other people use them as an example of a black metal band not being embraced by a narrow-minded black metal scene. Then we must ask what is motive for such empirically false claims.

Journalists now have more influence through their articles and interviews

As an experienced journalist, how important do you think are today the album reviews into helping shaping and maintaining scenes and new waves of bands/genres? Is there today the same tolerance in critique as it was in the past decades?

I don’t think it can be denied that the internet has made reviews of music much less relevant than in earlier eras because the audience can listen to content even before the review of that content is available. Book and film reviews are safer in that sense, because they are not so easily consumed online ahead or around the time of release. I think music reviews still have meaning though, because they give context to the art being released. Still, I think journalists now have more influence through their articles and interviews and that this is much more important today in terms of impact upon an audience.

How do you distinguish your love as a fan for an artist/record from a more “scientific” journalist’s approach while speaking about their art?

I like to think I am fairly objective when it comes to music, but in a way this hasn’t been a major factor in my books. Of course, I talk about what I think is great about certain records and so on, but the books aren’t really about me telling the reader what’s good and what isn’t. Rather I focus upon the historical impact of bands and music and then get the musicians themselves to talk about where their inspirations came from to create such works and what they feel about it in retrospect.

Black metal, has been a music genre that has had distinguished scenes and sound variations in different parts of the planet, making it one of the most creative metal genres. The new version of the book, expands deeper into this area of the sound. Have you found any common ground into the circumstances that led the shaping of the different scenes among different regions?

My position is that black metal is probably the most diverse and creatively vital forms of not only metal, but modern music. The range of bands that sit comfortably under that banner is incredible, from Blasphemy to Deathspell Omega, from Bathory to Mysticum, from early Ulver to Vlad Tepes, from Agalloch to Black Witchery and so on. To some extent the development of different subgenres of black metal was regional – as we’ve discussed, a strong local scene existed in Greece and so we had something like a ‘Greek sound’ manifest, to use one example.

But black metal was always an international movement, even before the internet, and I think that’s something I’ve tried to underline in this book. A single demo recorded and tape traded from fan to fan could end up having a profound impact on musicians on the other side of the globe. Examples of that include the Tormentor and VON demos, which travelled via tape traders from Eastern Europe and the US respectively to Scandinavia where they inspired many bands that followed.

Black metal, and metal in general, retains strong links across generations because of this combination of experimentation and traditionalism

Furthermore, as it is evident by many parts of the book, identity, has always been a core element of the black metal aesthetics. How do you feel about revival scenes and bands that always come forth from the underground? Do you think that they have their role into keeping the genre afloat in this chaotic world, or is it the never ending experimentation that pushes it through?

I definitely think they have a role both musically and culturally. I think black metal, and metal in general, retains strong links across generations because of this combination of experimentation and traditionalism. Not all music genres are so lucky. In hip-hop or dance music new movements regularly form but tend to be somewhat generational, so the kid who is listening to a new rap star probably isn’t listening to classics from the 1980s like Public Enemy.

In metal, new sounds are created but we do not abandon the old creations as a community and for that reason we have teenagers listening to the same bands – be it Black Sabbath or Mayhem – that people in their 60s listen to. So in the same way I think young bands that keep alive the 80s black thrash sounds are as important as the cutting edge groups creating more original material.

Black metal is ever-evolving, but the actual nature of black metal has been fairly consistent since the 1990s

If you could predict the future of black metal, where do you see it in 10 years, not only in its form and sound, but also as an underground scene?

My feeling is that black metal is ever-evolving, but the actual nature of black metal has been fairly consistent since the 1990s. It is defined by this duality we have discussed, with the experimental and pioneering bands balanced by those more conservative bands seeking to perfect older manifestations. In this sense, it is concerned with both the future and the past to an equal extent, so I can’t imagine it fracturing in the same way that some other genres have in terms of generation gaps. Culturally the biggest change probably came with the explosion of social media and the influx of fans from other scenes, such as hardcore, and it survived that intact.

This year is coming to an end, and as you know, the publications, journalists and fans, are preparing their end lists. Have you made up yours? Are there any albums that you enjoyed this year?

No, none at all haha. The last 12 months or so I’ve been solely listening to music from the last 40 years as part of this new book. So I’m the last person to ask about new music. Finally, I can begin to catch up with music from after 2022 now this book is being released.

The bombardment of content we experience makes books of more value than ever

In a today’s world of fast information, internet, podcasts and a little free time, how do you view the importance of books, especially in music, and how do you tackle this matter with Cult Never Dies?

My feeling is that the bombardment of content we experience makes books of more value than ever. I guess that’s been my gamble this last decade. These days people don’t have to pay for most of the content they consume, but when they do, especially as real music fans, they tend to want more luxurious and less disposable items. In the same way that people now choose vinyl or special edition CDs despite the proliferation of streaming, I think people choose to invest in high-quality books, alongside reading content on the internet and so on. That seems to be the case at least. Let’s hope it continues!

Is Cult Never Dies about to continue covering/publishing books dedicated exclusively to particular extreme metal sub-genres/scenes?

Absolutely! Cult Never Dies is dedicated in large part to publishing books dealing with the black, death and doom metal genres, as well as biographies of particular bands. I think we could comfortably release books on larger bands from ‘our world’ so to speak - for example, I would happily sell a book on Black Sabbath or Judas Priest, but probably not a book about Slipknot.

Final question, and I would like to thank you for your time! Any future endeavors that you are planning and you would like to share with us?

This book took up most of our time and energy and money as a publishing house this year, so we have a good deal of books that have been delayed and will be coming out in 2024 and 2025 including the Petrified fanzine anthology, a Christophe Moyen art book, the third volume of our Doom Metal Lexicanum series, a book on black metal merchandise history and a book on dungeon synth. Plus new official black metal merchandise.